I Love Sushi – An Traveling Exhibition by Japan Foundation in Chennai : Exploring All about the Sushi’s Brief History & Origin, Timeline, Evolution, Cultural & Types of Sushi / Narezushi – Japan’s Most Famous Cuisine (Updated)

– a journey through the delicious world of sushi

| CasualWalker’s Rating for I Love Sushi – An Traveling Exhibition by Japan Foundation in Chennai : | |

9.9 – Superb Awesome

|

“I Love Sushi” – a traveling exhibition was wonderfully organized by the Japan Foundation and inaugurated by Shri. Taga Masayuki San, the esteemed Consul General of Japan in Chennai, in collaboration with The Consulate-General of Japan in Chennai and ABK-AOTS Dosokai, Tamilnadu Centre at Lalit Kala Akademi to exhibit all about famous Sushi, history and culture.

In the midst of the global fascination with Japanese cuisine, the exhibition’s chosen theme is the iconic “Sushi.” A celebration of this delectable art form, the exhibition unfolds the rich history and cultural significance of sushi through life-sized models, including Nigiri-zushi, a typical sushi restaurant counter, and a captivating reproduction of a Kaiten-zushi – the conveyor-belt sushi.

Sushi’s – the Global Resonance

Sushi, recognized worldwide as a healthy, visually pleasing, and refined delicacy, epitomizes “Washoku” or Japanese cuisine. Acknowledged by UNESCO in its Intangible Cultural Heritage list, sushi serves as a cultural ambassador touring the world through this mobile museum. Beyond being a culinary delight, it becomes a medium to showcase Japan’s diverse food culture.

A Culinary Evolution: From Edo to the World

Originating over a millennium ago from Southeast Asia or Southern China, sushi made its way to Japan, evolving significantly over the years. The exhibit beautifully narrates the story of sushi’s transformation, influenced by Japan’s abundant natural resources, innovative ideas, and the relentless pursuit of delectable flavors. While today’s nigiri-zushi is the go-to image for many, it’s fascinating to learn how it emerged about two hundred years ago in Edo, now Tokyo.

Despite sushi’s global popularity, there’s more to discover. This exhibition aims to unveil the intricacies of sushi’s appeal, providing a visual guide to its origins in Japan and its adaptation to different environments, cultures, and lifestyles worldwide.

I Love Sushi

Established in 1972, the Japan Foundation creates global opportunities to cultivate friendship and ties between Japan and the world through culture, language, and dialogue. The Foundation operates programs in the fields of arts and cultural exchange, Japanese-language education overseas, and Japanese studies and intellectual exchange. As a new cultural exchange program, we are delighted to present a touring exhibition “I Love Sushi” that focuses on sushi, the most popular Japanese cuisine around the world.

In 2013, UNESCO inscribed washoku-Japanese cuisine on its Intangible Cultural Heritage list, and sushi is an archetypal example. Sushi is a refined and healthy food that looks good and tastes good, and it has already become a familiar item on menus worldwide. From its roots in Southeast Asia or Southern China, sushi reached Japan over a thousand years ago. Since then, sushi has radically changed, taking advantage of the abundance of natural resources found in and around the islands of Japan, of the application of knowledge and ideas to sushi, and of the never-ending Japanese drive to try good-tasting foods at the earliest opportunity. The type of sushi that first comes to mind for most people today is nigiri- zushi, which emerged about two hundred years ago in Edo, the city that we now know as Tokyo.

Sushi has now spread outside Japan’s borders and is enjoyed around the world. But although it has become a familiar food, many people have only discovered a few of its attractions. This exhibition aims to provide an in-depth visual guide to the appeal of sushi. It includes the chance to learn about how Japan took in sushi in its original form, and how it modified sushi to suit the natural environment, culture, and lifestyles of individual areas. The exhibition includes a simulation of a visit to a sushi shop in Japan. People who know little about sushi will greatly enjoy the exhibition, and keen fans of sushi will find it fascinating too. And we very much hope that through sushi, the exhibition will also communicate something about the history and customs of Japan.

Introducing Sushi

Today, almost everyone thinks of sushi as Japan’s representative cuisine, but its origins were actually elsewhere. Some scholars point to origins in the plains of Southeast Asia or Southern China, but the details are unknown. We do know that sushi is mentioned in the oldest document produced in Japan, which was written in the eighth century, and we can be sure that sushi came across the sea from China, reaching Japan well over a millennium ago.

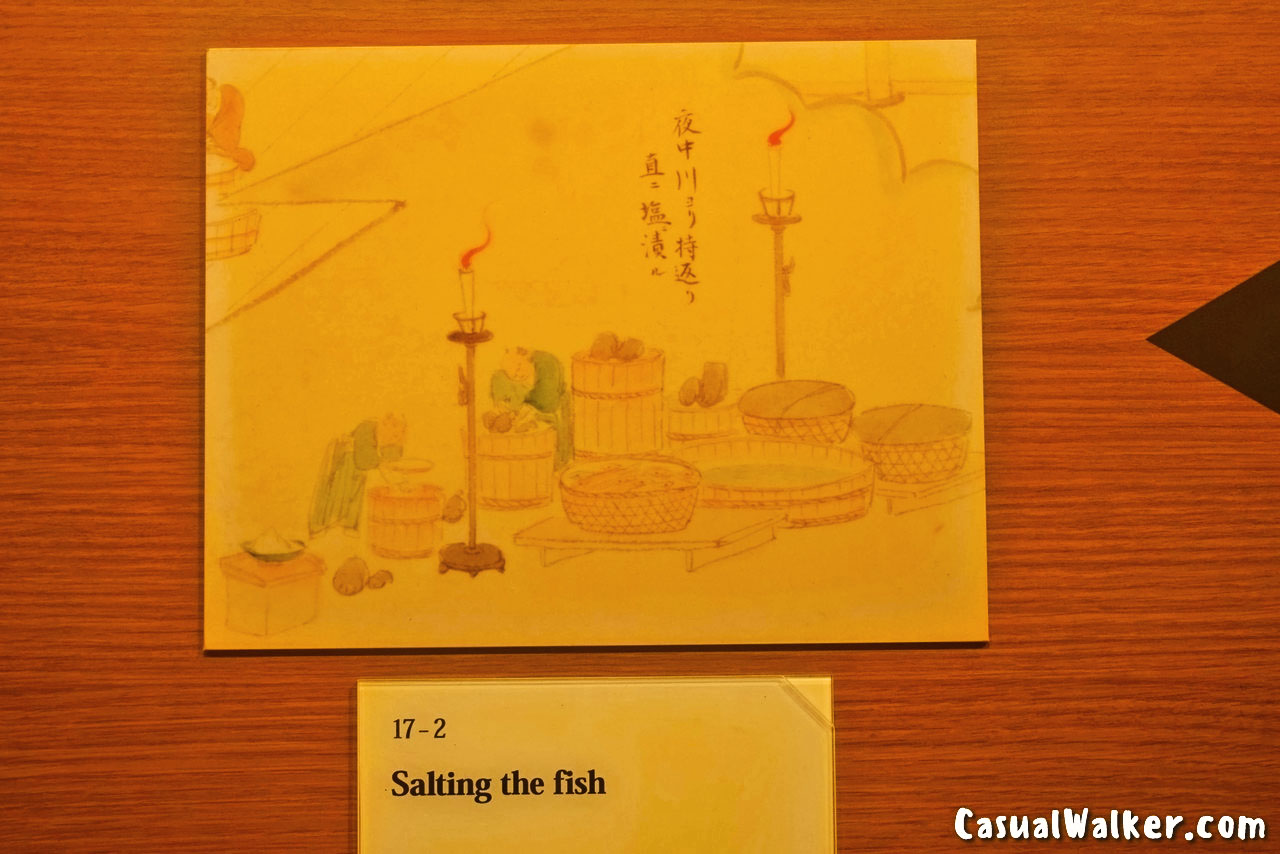

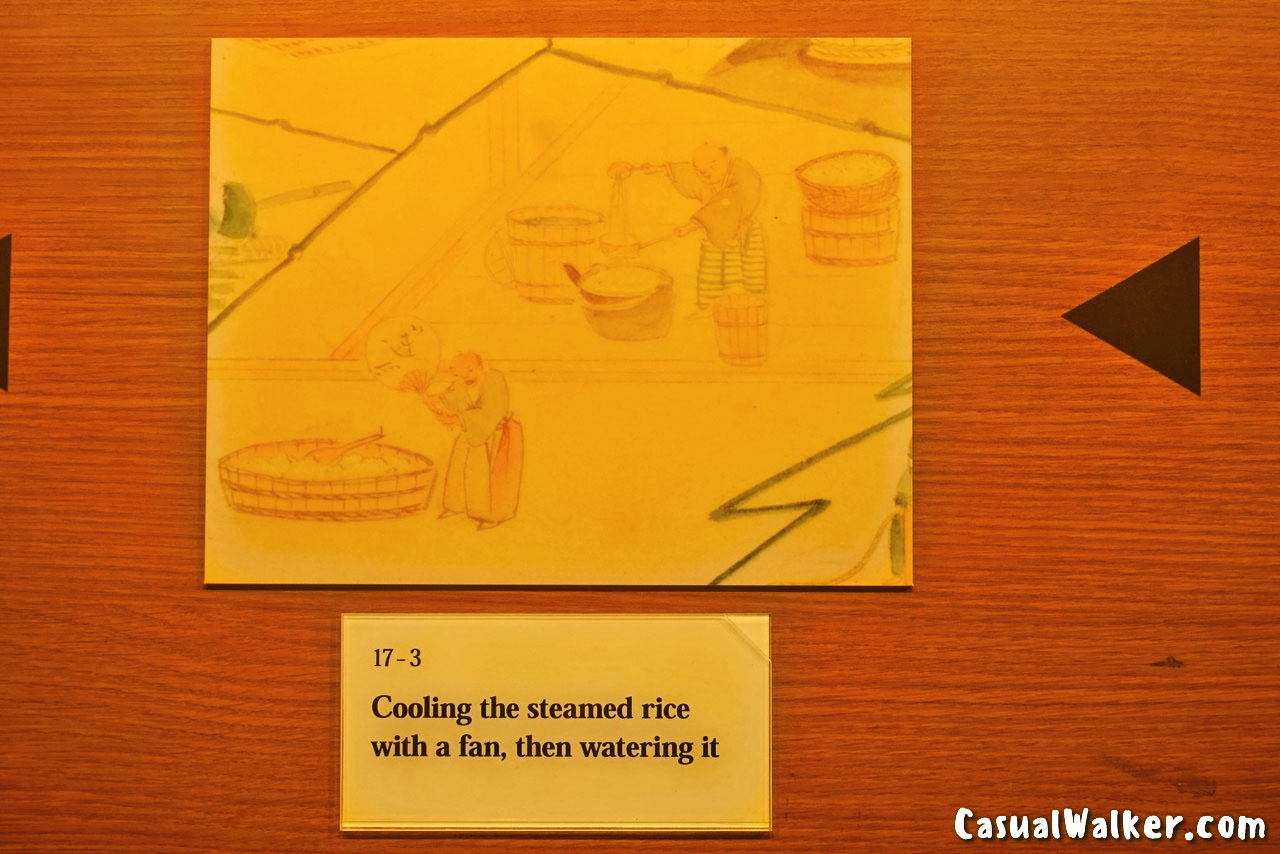

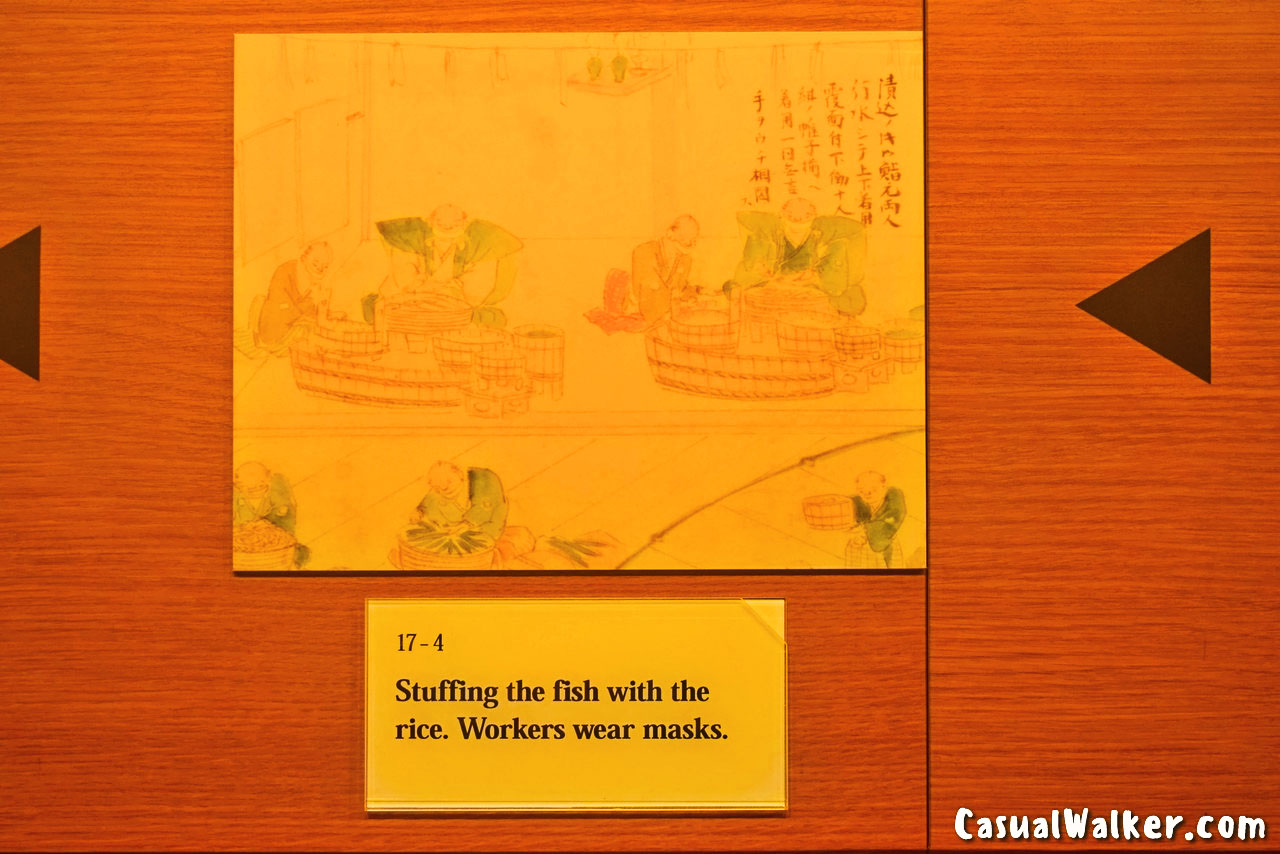

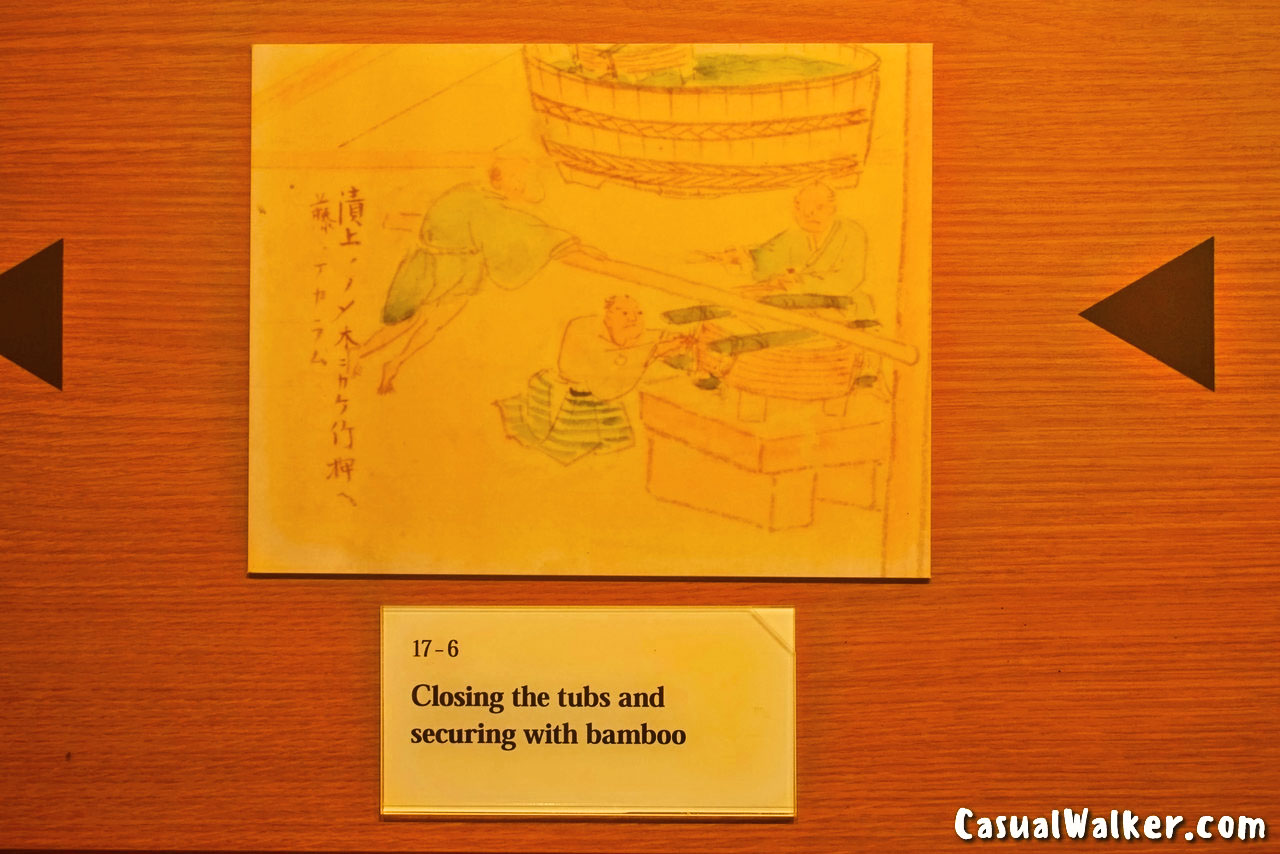

The sushi in those days was made by placing salted fish in a wooden tub or bucket with cooked rice and leaving it to mature for several months. Such fermented sushi is now called nare-zushi. (The “-zushi” in compound words like nare-zushi has the same meaning as “sushi.”) With nare-zushi, only the fish was eaten. The rice was used for fermentation and was originally thrown away after the fish had matured. In about the fifteenth century, people began to eat the rice along with the fish. Demand for sushi that could be ready for eating at an earlier stage then led to flavoring the fish directly with vinegar instead of producing the flavor through fermentation. That innovation triggered sudden growth in the types of sushi. Nigiri-zushi eventually emerged in Edo, present-day Tokyo, in around 1820-30. Since then, when people hear mention of sushi, nigiri-zushi is usually the type of sushi that they think of. Early nigiri-zushi was inexpensive, and each piece was about three times the size of the typical nigiri-zushi today.

The use of fresher fish for nigiri-zushi, and the current standard size of about 15-20g only became regular features of sushi after World War II. Soon after, in the 1960s, Japan’s economy grew strongly and nigiri-zushi went increasingly up-market, reborn as a luxury item. Today, however, nigiri-zushi is available to suit all budgets. In contrast to nigiri-zushi, however, the various types of sushi that people once made at home are at risk of dying out.

Sushi and Tuna

Many Japanese would say that tuna is the king of nigiri-zushi. Surprisingly, tuna-known in Japan as maguro-arrived late on the scene, and did not come into significant use for sushi until the nineteenth century. Tuna had been shunned because of its greasiness, and it was a cheap ingredient. However, when it was used for nigiri-zushi, the situation changed and it became more popular. Edo people enjoyed its lean red meat, and often pickled it in soy sauce to preserve its freshness, calling the pickled tuna zuke. The fatty part of the called toro- was avoided because it spoiled easily, so it was often boiled or discarded. Today’s generation would find that incredibly wasteful. People only began eating toro raw after refrigeration technology improved in the 1960s. After that, demand for toro and fresh tuna soon soared, and it became an indispensable part of sushi. Pacific bluefin tuna (kuromaguro or honmaguro) gained a reputation for high quality, and it is seen as the top fish for nigiri-zushi. Nakahara Ippo, writing about a sushi shop that serves Edo-mae nigiri-zushi, said that “of all the different types of nigiri-zushi, tuna is the only one that really hits the spot.” That is a sentiment that a large number of people would agree with.

Japan is the world’s largest consumer, but people from other countries also enjoy tuna. Today, about 70 percent of Japan’s Pacific bluefin tuna production consists of farmed fish, and the trend for full life cycle aquaculture is growing.

Pacific Bluefin Tuna (kuro-maguro or hon-maguro)

Pacific bluefin is the largest among the five staple types of tuna put on the table (pacific bluefin tuna, southern bluefin tuna, bigeye tuna, yellowfin tuna, and albacore tuna). Large specimens can be over 3 meters long and weigh over 700 kg. It is caught mainly in the northern hemisphere, particularly in the Pacific Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean, including the Mediterranean. Bluefin tuna are migratory predators, eating other fish and crustaceans. Pacific bluefin is a highly valued fish popular for sushi and sashimi, so resources need to be managed to prevent overexploitation. International efforts to manage resources are in progress.

150 Examples of Today’s Sushi

In the nineteenth century when nigiri-zushi was launched, people favored fish with a refreshing flavor like kohada and aji, considering fatty fish like tuna to be low-grade. However, lifestyles changed over the years, and tastes changed with them. Today, the fattiest cut of tuna-is considered the most lavish cut for sushi. The neta placed on the rice has also become more varied, including vegetables and meat in addition to fish and shellfish. Kaiten sushi restaurants in particular are constantly extending their menus. Here we present 150 examples of sushi, mainly nigiri-zushi, that are popular today.

Journey Through Time: Sushi during the Edo Period

Delve into the early 19th century Edo period (1603-1867), where Nigiri sushi took center stage, becoming a culinary sensation. Witness the presentation of ukiyo-e art, emaki scrolls, and street stalls, offering a vivid snapshot of the historical context in which sushi flourished.

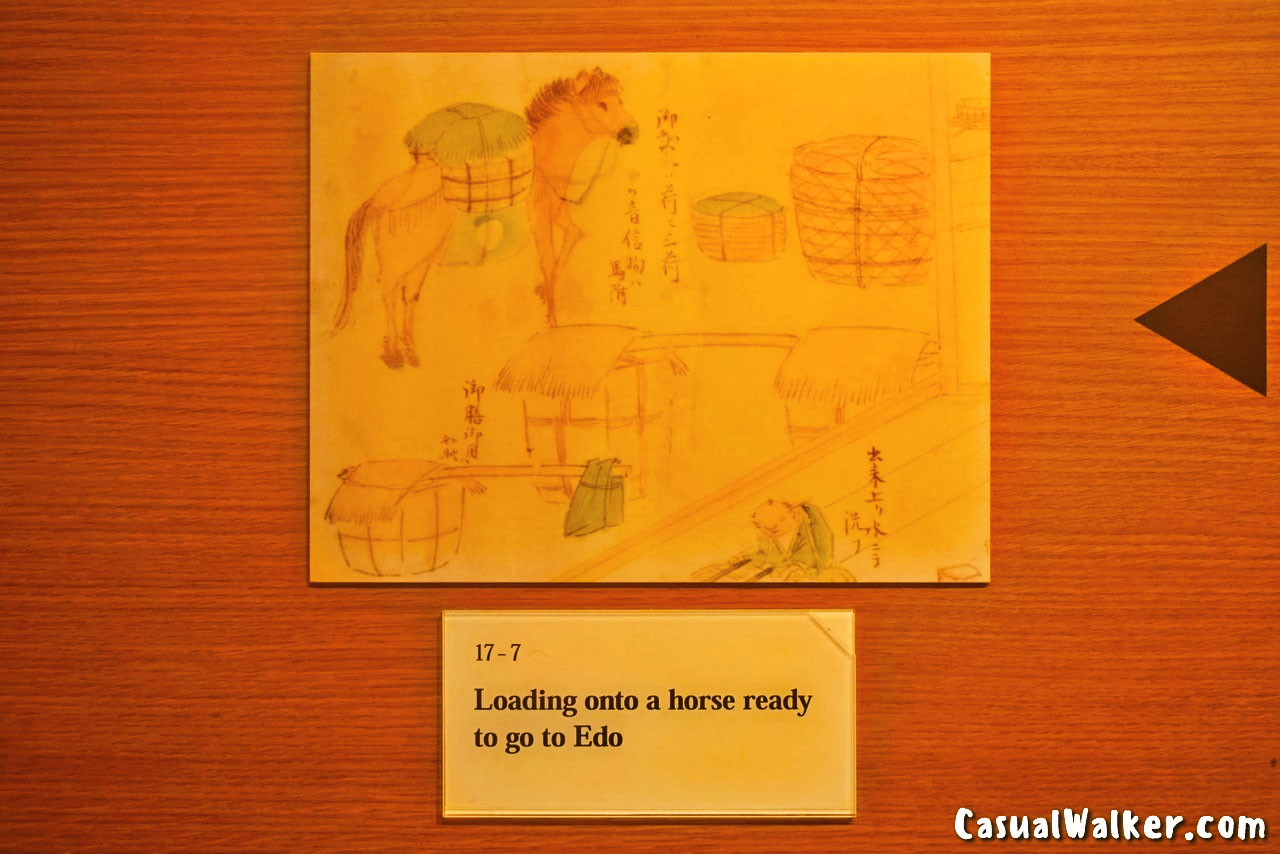

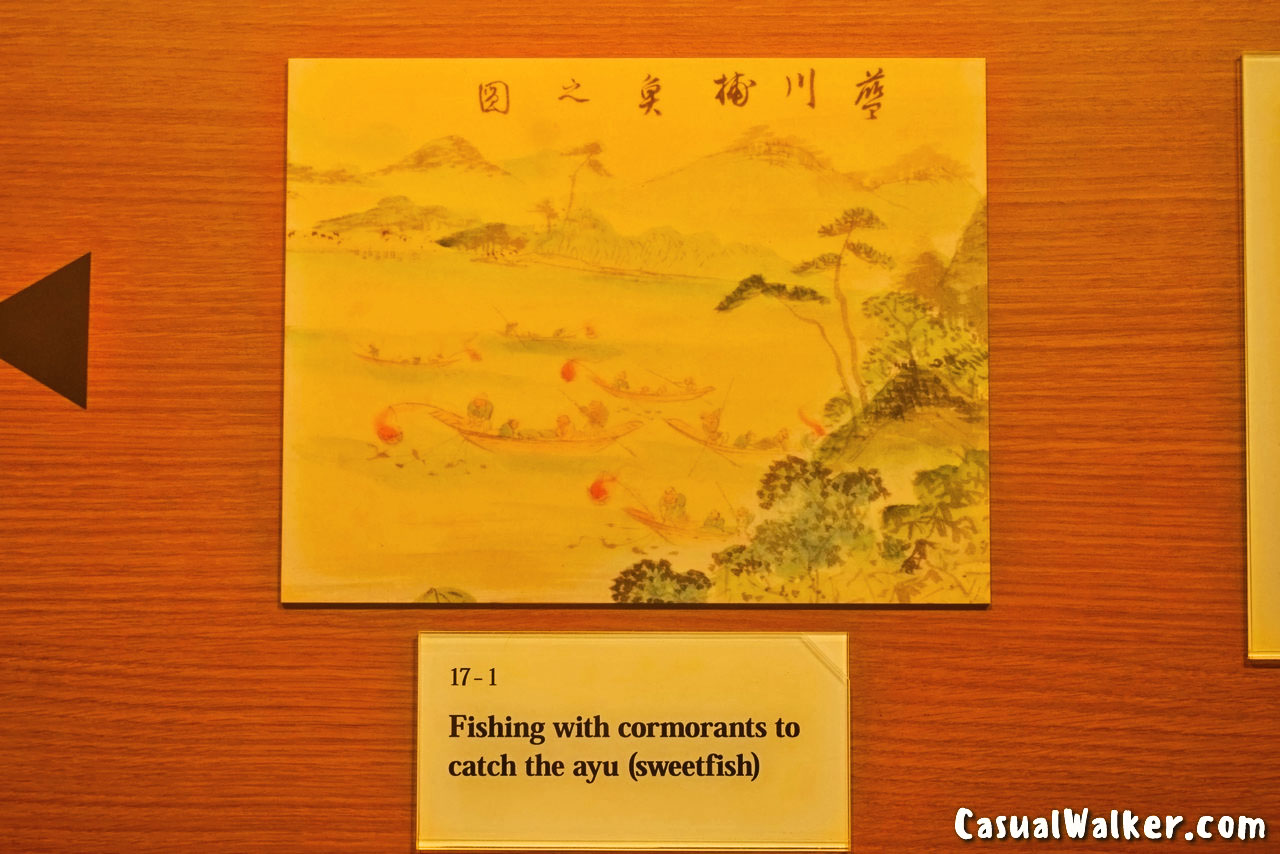

At the beginning of the Edo Period, sushi was still a fermented dish, produced by traditional methods. Many feudal lords included sushi in the tributes they presented to the shogunate in Edo, and the dish selected would be a local sushi delicacy produced by fermentation. The long journey required to transport the sushi to Edo could be used as part of the fermentation process.

That did not apply to the common people, who could use their ingenuity to simplify the production process or take shortcuts that brought the sushi to the table faster. Using vinegar instead of fermentation to flavor the fish soon became mainstream. Eventually, the accumulation of changes led to the appearance of Edo-mae nigiri-zushi-sushi made with seafood from the seas in front of Edo-presented on rice that had been flavored with vinegar.

The culture of nigiri-zushi, with its bright colors and elegance, changing with the seasons, is not the culture of the shogun and the daimyos, nor of the imperial court in Kyoto, it is the creation of the ordinary people. The advent of nigiri-zushi led to the popularity of sushi stalls, where people would stand to eat the pre-prepared nigiri-zushi. At around the same time, expensive luxury sushi restaurants also appeared, serving sushi far out of the reach of most people’s pockets. But rather than being resented, they were welcomed by the common people, who saw them as something to aspire to.

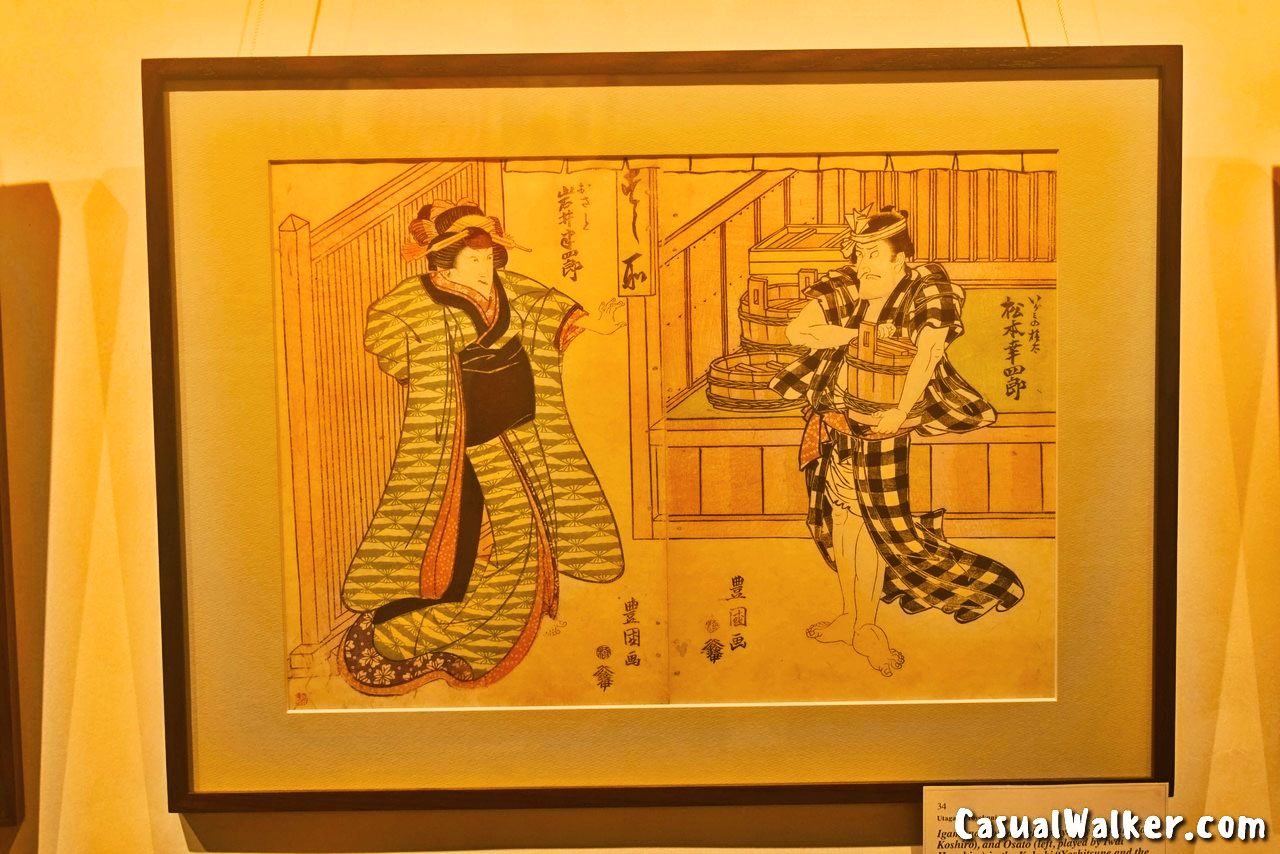

The graphic illustrations of ukiyo-e were another cultural feature of this age popular with the masses. There are a small number of ukiyo-e paintings and prints that depict sushi. Most of them show nigiri-zushi, demonstrating how much ordinary people loved this new type of sushi, and the extent to which it had become a part of their everyday lives.

Sushi Depicted in Ukiyo-e Art

Hinohara Kenji

Chief Curator of Ota Memorial Museum of Art

Ukiyo-e art was produced for the general populace from the latter half of the seventeenth century to the end of the nineteenth century. Most ukiyo-e works were mass-produced using woodblock printing techniques and sold at the inexpensive price of between 500 and 1,000 yen (approx. between $4 and $8) per print. Ukiyo-e became a popular diversion, mainly depicting topics with general appeal, such as lively tourist spots, beautiful women, and popular Kabuki actors.

The most famous work of this kind is probably Takanawa 26th Night Revelers, from Famous Places in the Eastern Capital (No.21) by Utagawa Hiroshige. This depicts the annual event of Nijuroku Ya Machi in which people celebrated the rising moon on the night of July 26. It shows many sightseers gathering on the coast to view the rising moon, as well as various stalls lined up offering the crowd items such as fruit, grilled squid, tempura, soba noodles, dango dumplings, and sweet shiruko porridge. Among them is a sushi stall. Lots of nigiri-zushi are lined up on display on the stands, and sightseers likely snacked on sushi in place of their evening meal on this occasion. This clearly shows that sushi was a popular fast food of the day that was convenient for ordinary people to buy and enjoy, much like the other street foods on offer.

Sushi also appears frequently in ukiyo-e depicting beautiful women in everyday situations. Good examples that clearly convey the characteristics of sushi are three works by Utagawa Kuniyoshi-Sushi, from The Universe of Women (Shinramanzo) (No. 23), Takeout Sushi, from Women in Benkei-checked Fabrics (No. 24), and Fukagawa Susaki Benten, from Seven Gods of Good Fortune, Benten of the Eastern Capital (No. 25). These prints reveal details from the period when they were created, such as the sushi toppings (neta), the way the pieces of sushi are shaped (nigirikata), and how they are arranged on the plate (morikata).

Depictions of sushi and sushi stalls in ukiyo-e works like these are surprisingly rare compared to the huge number of ukiyo-e prints that were produced overall. Furthermore, there are almost no ukiyo-e prints that focus on the sushi itself. Sushi and New Year’s Sake (No. 22) is an exception. This is also the case for other popular foods besides sushi, such as soba noodles, tempura, or eel (unagi). Ukiyo-e art depicted things that were the object of the general populace’s yearning and fascination, so common, everyday things like food did not attract as much attention.

Sushi Stall

Ukiyo-e artist Kitagawa Utamaro’s The Sparrows of Edo, a Picture Book (right) includes a depiction of a sushi stall. Nigiri-zushi had not yet become popular, so the stall was selling a range of oshi-zushi, and behind the stall is a figure carrying a wooden press used to produce the sushi. Some forty years after the publication of this book, the scene would change when nigiri-zushi appeared. Sushi stalls became highly popular, with customers choosing whatever they wanted from the pre-made sushi on the stall, and generally eating it on the spot, standing up. The most popular types seem to have included tuna akami, aji, kohada, akagai, and torigai.

These stalls were informal, the food was ready to eat straight away, and it was cheap (starting from 4 mon for one piece, representing about 120 yen (equivalent to $1) in today’s money). Tamago (thick omelet)- maki was the most expensive. Nigiri-zushi was effectively the mainstream fast food of that period. At about the same time, some sushi chefs set up shops with imposing entrances, taking their operations up-market. Counter seating was installed inside such restaurants, apparently hoping to benefit from the popularity of the sushi stalls. Large numbers of sushi shops sprung up, but the sushi stalls remained to serve the mass market until the beginning of the twentieth century when they began to decline.

Sushi Today – Kaiten Sushi : Conveyor Belt Sushi Restaurants

In today’s Japan, Sushi is undeniably an everyday food. It achieved that status partly through take-out sushi being on sale at supermarkets and other shops, but also to a large extent because of the popularity of kaiten sushi (conveyor belt sushi) restaurants. Both concentrate mainly on nigiri-zushi. They keep prices low, but they are fully committed to raising the quality of the sushi.

Sushi in Virtual Reality: A Unique Experience

The exhibition goes beyond the visual and offers visitors a chance to step into the shoes of a sushi connoisseur. An interactive area allows you to experience a virtual sushi restaurant, providing a taste of the culinary journey in the digital realm. The video was filmed in cooperation with Kizushi, a long-established sushi shop located in the Ningyocho area of Tokyo that carries on the Yohei Sushi tradition. It is fascinating to watch the skillful handling of the sushi ingredients by a chef who has learned techniques passed down in an unbroken link through establishments serving Edo-mae nigiri-zushi, and see the delicious-looking sushi that results.

Sushi installation

Lined up together, the range of colors in nigiri-zushi and nori maki-zushi make a beautiful sight that stands out even among the bright colors of the many different kinds of an individual type of sushi is simple, but when arranged in a serving tub, they come together to create a harmony that makes any day feel like a festival. Japan is renowned for the effort put into making food look attractive, but seeking out beauty is probably the shortest route to finding more delicious food. This sushi installation is an attempt to display sushi as if it were contemporary art. The installation focuses mainly on nigiri-zushi, incorporating 30 pieces of each of 31 different types of sushi to make an overall arrangement of 930 pieces.

The first kaiten sushi restaurant was launched in Osaka in the late 1950s. The system of serving nigiri- zushi on individual plates that were carried around the restaurant on a conveyor belt was fun, and using plates with different colors or patterns to indicate the prices made it easy to see how much you were going to be charged for the sushi that you chose from the belt. These ideas spurred the popularity of these restaurants, and Expo 70 Osaka provided the opportunity to show kaiten sushi to people from all over the world. The image of nigiri-zushi as an expensive luxury was transformed by kaiten sushi, and sushi became an increasingly popular choice for families going out for a meal. More recently, a number of restaurants have built up nationwide chains, using their purchasing power and ideas such as robotic sushi chefs to keep prices low. Menus have expanded, and it is no longer unusual to see sushi restaurants offering desserts and even ramen noodles.

Nigiri-zushi is by no means the only sort of sushi available. Each region of Japan has its own distinctive sushi dishes that have been developed over long periods and reflect local features, climate, and customs. A few of these dishes have been brought back into the spotlight as part of efforts to revitalize local culture, but local forms of sushi produced in ordinary homes are at risk of disappearing altogether. Sushi dishes like that are a highly valuable part of Japan’s heritage, but the people who make them are often completely unaware of their value. If that situation continues unchanged, the day will come when that unique sushi is no longer made. And once it disappears, any attempts to revive the dish based solely on fond memories of what it tasted like are fraught with difficulties.

Japan is blessed with a rich natural environment and distinct seasons. It also has a plentiful supply of fish of many different types and a large variety of edible wild plants. Every single one of them has been used in Japanese cuisine and sushi. Varied sushi dishes that have been produced continuously for centuries with little modification to methods provide a wealth of culinary delight that can still be enjoyed today. It is up to us to make sure that we never forget them.

The Japan Foundation’s “I Love Sushi” exhibition is not just an event; it’s a culinary journey to dive into the flavors, history, and cultural richness of sushi – a journey that transports us to the heart of Japan’s culinary brilliance.

Also, check our Similar Interesting Photo Stories:

Asuras – Swarna Kolu / Golu, an Indian mythological Dolls & idols Exhibition at Thejus, Chennai

Puppet exhibition by Dhaatu Puppet Theatre, Bangalore / Bengaluru

Related Stories

Related Stories