Bhoota Kola (Daiva Aradhana) / Bhootaradhane, or Bhootaradhana: Complete Guide to Coastal Karnataka’s Ancient Guardian Spirit Worship Tradition in Tulunadu Culture of Dakshina Kannada, as Seen in Kantara Movie – History, Panjurli & Other Daivas, Ritual Practices, Best Temples in Mangalore-Udupi-Kerala to Experience Bhoota Kola, Festival Times & Visitor Tips (Updated)

– everything about tulu culture’s sacred bhootaradhane tradition

The flickering torches, rhythmic drumbeats, and dancers moving in trance-like states – these powerful scenes from the blockbuster Kannada film Kantara introduced millions worldwide to Bhoota Kola / Buta Kola / Bhuta Kola, an ancient spiritual tradition that has been the cultural heartbeat of coastal Karnataka for centuries.

Bhoota Kola: Sacred Spirit Worship

Bhoota Kola / Buta Kola / Daiva Kōlā, also known as Bhootaradhane or Daiva Aradhana, is a ritualistic spirit worship practice deeply rooted in the coastal districts of in the Tulu-speaking regions of southwest Karnataka—covering South and North Kanara, particularly Dakshina Kannada, Udupi, and parts of Kasargod in Kerala. This region, known as Tulunadu, has preserved this sacred art form across generations, making it an integral part of the area’s cultural identity.

The term “Bhoota”, in Tulunadu, Bhootas are protective divine spirits – guardians who safeguard communities, resolve disputes, and ensure prosperity. They represent benevolent forces rather than malevolent entities, serving as intermediaries between the physical and spiritual realms.

They are supernatural beings—mostly benevolent, though occasionally fierce—believed to guard the land, protect livestock, drive away illness, and bring rain. The Tuluva people venerate more than 500 distinct Bhutas.

The Bhoota Kola tradition centers on deities with distinctly human origins, contrary to popular misconceptions linking them to ancient Kadamba rulers. These deities fall into two categories: animistic spirits like Panjurli (the boar deity featured in Kantara Movie) and human figures who died fighting injustice and achieved divine status posthumously.

The kola operates as both spiritual ceremony and communal judiciary, where possessed oracles speak fearlessly about community grievances and family disputes, delivering verdicts that function as a folk justice system. Despite its sacred nature, the practice welcomes respectful outsiders, with entire villages gathering during performances and researchers often receiving the deity’s first blessings. The season runs from post-Deepavali through May, with each family shrine (sthana) holding kolas on fixed dates, easily found through banners across Mangaluru in December.

The ritual’s spiritual integrity demands strict adherence to ceremonial protocols—makeup application, costume donning, pardana singing by designated families, mask bestowal, and systematic deity departure—all tied to specific dates and locations. This distinguishes Bhoota Kola from performance arts like Yakshagana or Veeragase, which can be staged periodically. The possession element forms the belief system’s core, explaining why casual impersonations by fans have deeply offended tradition practitioners who view it as violating sacred boundaries rather than cultural appreciation.

Bhutas can be grouped into several categories:

Totemic spirits such as Panjurli (the wild boar spirit), Pilchandi (the tiger), and Nandikona (the bull).

Mythological beings linked to Hindu deities like Lord Shiva and the Mother Goddesses. Shiva, revered as Bhutnatha—the Lord of Spirits—rules over a host of ganas and bhutas.

Deified heroes or martyrs, human beings who died valiantly or unjustly, often defending noble causes. These spirits are especially revered by the lower castes, for they symbolize resistance, suffering, and the social struggles of the oppressed.

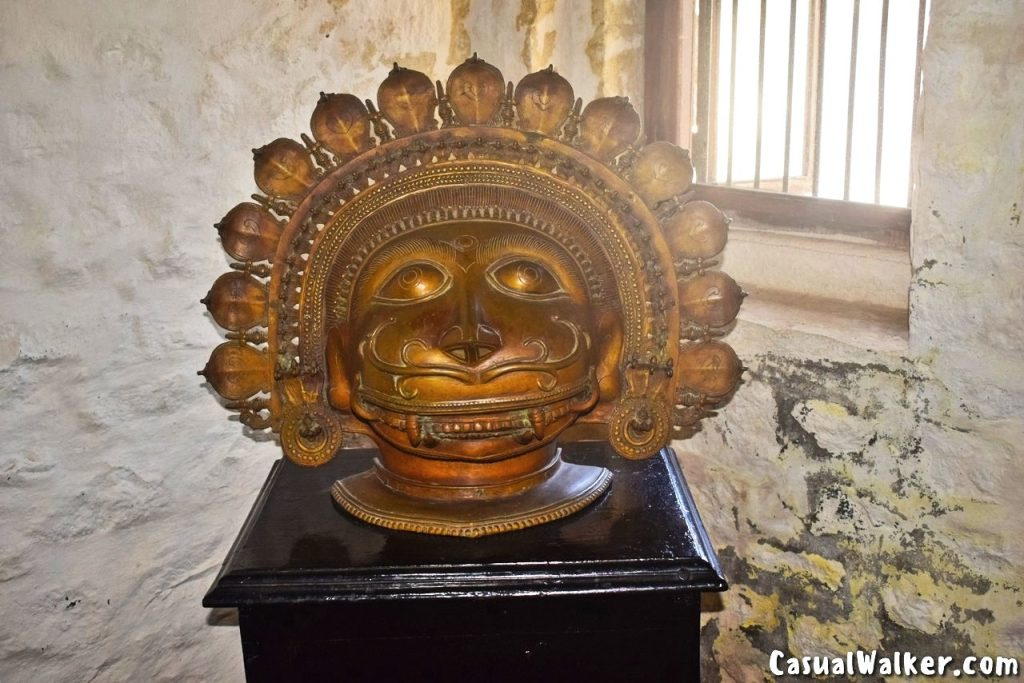

A Bhuta shrine need not always be a sculpted image—it can exist within a tree hollow, a wall recess, or even a household corner. Each year, communities come together to honor these spirits in the grand Bhuta Aradhana festivals, where families, villages, and devotees participate in colorful ceremonies, music, and ritual dance. The small figurines of women and the Panjurli boar on display here are traditional offerings made during these sacred rites.

Historical Background and Cultural Evolution

Bhoota Kola’s origins stretch far deeper than written documentation, rooted in India’s ancient animistic and folk traditions that predate organized religion.

The worship of protective spirits, nature deities, and ancestor veneration has been integral to South Indian culture for millennia, predating the arrival of Aryan influence in the region.

Relationship with Vedic and Puranic Traditions

In the Puranas and epics like the Mahabharata and Ramayana, divine beings are born to fulfill specific prophecies, recognized even in their mothers’ wombs, with celestial music (mangala vaadya) announcing their arrival. Their births are celebrated by other deities, and they achieve greatness by virtue of their divine lineage.

Bhootas, in contrast, represent a more egalitarian spiritual philosophy. They are individuals – often from marginalized communities like the Koraga tribe – who faced hardships, injustice, or untimely deaths. Their transformation into protective spirits occurred posthumously, through community recognition of their struggles and righteousness. This democratization of divinity stands apart from the hierarchical structure of Vedic and Puranic deities.

Parallels with Other Indian Traditions

Bhoota worship shares similarities with other regional folk traditions across India

- Theyyam of Kerala – A closely related form of spirit worship

- Yakshagana – The coastal Karnataka dance-drama that influenced Bhoota Kola’s theatrical elements

- Nagaradhane – Serpent worship prevalent in the same region

- Gram Devata worship – Village deity worship found throughout rural India

- Kul Devata traditions – Family deity worship common across Hindu communities

The concept of spirits inhabiting natural elements – trees, stones, water bodies – resonates with the Vriksha Devatas (tree spirits) and Naga worship found in ancient Indian texts. The recognition of divine presence in nature forms a common thread connecting Bhoota worship to broader Indian spiritual consciousness.

Medieval Period and Social Evolution

During medieval times, as feudal structures solidified in coastal Karnataka, Bhoota worship evolved into a complex system incorporating elements of social governance. The practice absorbed influences from various communities – creating a syncretic tradition unique to Tulunadu.

The oral tradition of Paddanas developed during this period, serving as both spiritual narratives and historical records of the region. These folk epics preserved stories of heroic sacrifices, and divine interventions, offering insights into centuries of Tuluva social life.

This Tuluvas worship was actually a sophisticated system integrating spiritual worship, community governance, conflict resolution, and artistic expression.

Preservation Through Generations

This Bhoota worship retained its essential character. The tradition survived because it fulfilled genuine community needs: providing justice, offering psychological security, maintaining social cohesion, and connecting people with their ancestral land and heritage.

Scholars have identified over 400-600 distinct Daivas or Bhootas in Tulunadu, though some argue the number could exceed a thousand when accounting for regional variations and different names for the same spirit. For instance, Panjurli, the revered wild boar spirit, is known by 31 different names across various regions. This diversity reflects centuries of organic evolution as communities adapted the tradition to local contexts.

The Deep Significance of Bhoota Worship

Justice and Social Governance

One of the most remarkable aspects of Bhoota Kola is its role in delivering justice. In many rural villages, people still prefer consulting a Bhoota over approaching formal courts. The divine judgment delivered through the Daiva Patri (medium) is considered binding and truthful, shaping social discipline and ethical behavior in these communities.

This tradition has created an alternate system of conflict resolution where family disputes, property disagreements, and social conflicts are resolved through spiritual intervention. The decisions made during Kola ceremonies are respected across caste and class boundaries.

Protection and Prosperity

Different Bhootas govern specific aspects of human welfare and natural phenomena:

Panjurli – The wild boar spirit protects agricultural lands from wild animal attacks, particularly from wild boars. This Daiva gained global recognition through Kantara.

Pilichamundi – Appearing in tiger form, this Bhoota safeguards cattle and prevents crop theft from predators.

Bobbarya – Fishermen offer prayers before sea expeditions, seeking protection during their voyages.

Mariamma – Believed to control epidemic diseases and public health crises.

Korage – Protects livestock from deadly diseases and ensures animal welfare.

Nandigona – Manifesting as a bull, this spirit oversees agricultural prosperity.

The Ritual Practice: Creating Sacred Space

Timing and Atmosphere

Bhoota Kola ceremonies typically occur at night, transforming ordinary spaces into what scholars call “liminal spaces” – temporary realms where the material and spiritual worlds intersect. The dimly lit atmosphere, created by torches and oil lamps, combined with the darkness of night and the open field setting, generates an otherworldly ambiance that facilitates spiritual connection.

The Daiva Patri: Medium of Divine Communication

The Daiva Patri, also called Pātri or Māni, serves as the vessel through which Bhootas manifest in the physical world. Becoming a medium isn’t merely a hereditary position – it requires the Bhoota’s blessing and approval, which can take years to receive. The practice often runs through families for multiple generations, with knowledge passed from grandparents to grandchildren.

Preparation Requirements

- Ritual bathing in cold water

- Wearing sacred white clothes (madi)

- Adorning specific flowers and jewelry

- Following strict dietary and lifestyle restrictions

- Maintaining physical and spiritual purity

The Transformation Process

During the ceremony, as traditional instruments like clarinets (pipes) and drums reach their crescendo, the Patri begins the transformation. Holding areca flowers, they stand in a designated sacred circle. The atmosphere intensifies as the music grows louder, and the Patri’s movements become increasingly vigorous.

The body starts trembling, areca flowers are rubbed on the face in circular motions, and within minutes, the transformation completes – the Bhoota has entered the medium’s body. The possessed Patri then performs extraordinary feats: running flaming torches across bare skin, walking on beds of hot coal, and speaking in elevated language forms that require interpretation.

Paddanas: The Epic Oral Tradition

Paddanas are epic folk ballads that form the backbone of Bhoota Kola’s narrative tradition. These songs narrate each Bhoota’s origin story, describing their journey from human or animal form to divine status. Unlike Vedic gods who are reincarnations of existing deities, most Bhootas were ordinary individuals from marginalized communities who faced hardships and conflicts, meeting untimely deaths or disappearances.

These oral epics preserve Tulunadu’s cultural history, passing down stories, values, and social commentary through generations. The Paddanas are performed by narrators or the Patri themselves during ceremonies, creating an immersive storytelling experience.

Madhyasta: Bridge Between Worlds

An intermediary called the Madhyasta (mediator) facilitates communication between the possessed Patri and devotees. This role is crucial because the Bhoota often speaks in archaic language forms or different Tulu dialects that require translation. Family elders typically serve as mediators during household ceremonies.

The Areca Flower Oracle

During consultations, the Patri holds areca flowers and breaks petals after listening to each devotee’s problem. The number of petal pieces serves as an oracle:

- Odd number of pieces: favorable outcome

- Even number of pieces: alternative measures needed

This practice combines spiritual guidance with a tangible divination system that devotees can understand and act upon.

Kantara: Ancient Tradition Meets Modern Cinema

Rishab Shetty’s 2022 film Kantara brought unprecedented global attention to Bhoota Kola. The movie’s climactic sequences featuring the Panjurli and Guliga Daivas weren’t merely cinematic spectacle – they represented authentic portrayals of actual Kola ceremonies, from the costumes and makeup to the ritualistic movements and the spiritual intensity.

The film’s success sparked worldwide curiosity about this ancient practice. International audiences, previously unfamiliar with Tuluva culture, began researching terms like “Daiva Aradhana,” “Panjurli,” and “Bhootaradhane.” The movie demonstrated how traditional practices could be respectfully represented in popular media while maintaining their sacred essence.

Kantara also highlighted the environmental and social themes embedded in Bhoota worship – the connection between humans and nature, the importance of preserving forests, and the democratic spirit of communities where divine intervention transcends social hierarchies.

The Democratic Spirit of Kola Ceremonies

The Patri, commands absolute respect from all attendees regardless of their social status. When the Bhoota speaks, wealthy landlords and Brahmins alike listen with equal reverence. The ritual space becomes genuinely egalitarian, where only the Bhoota’s authority matters, not human hierarchies.

Physical Elements and Ritual Objects

The Bhoota Sthana

Traditional households maintain a Bhoota Sthana – a dedicated room or corner housing metal and wooden masks representing their family or community Daivas. These masks, used during ceremonies, are considered sacred objects infused with divine presence.

Bhoota Kola Invocation

Each bhoota has a specific sphere of influence and is associated with particular families or villages. During the kola ceremony, the bhoota impersonator invokes the host family’s guardian spirit and answers devotees’ queries. The Bhoota Kola season runs from November through late May, drawing crowds from near and far who bring offerings, doubts, and prayers for blessings or favors.

Sacred Setting and Initial Rituals

Ceremonies are held in decorated pandals adorned with palm and mango leaf festoons and colorful rangolis. The ritual begins with the host offering coconut oil to the spirit medium (patri) for a ceremonial bath. The medium then applies makeup using plant-based pastes, with each bhoota having distinctive costumes that symbolize its unique characteristics. As the medium prepares, female family members sing pardanas—catchy Tulu ballads narrating the bhoota’s story, heroic deeds, and powers. These songs help the medium embody the spirit while setting the audience’s mood. Meanwhile, other family members craft the gown from palm leaves.

Transformation and Invocation

The medium dons the dress and ornaments: ear and shoulder coverings, waist pieces, bangles, anklets, and headgear. The most crucial ornament is the gaggara (metal anklet), whose deep metallic sound accompanies the ritual. As musicians play drums and wind instruments, the dancer taps his feet rhythmically to invoke the spirit.

Divine Possession and Blessings

Once possessed, the medium roars and jumps wildly before being calmed with tender coconuts. The spirit then addresses the host, asking why it was summoned. Devotees share their troubles, and the possessed medium listens patiently, offering guidance. Acting as both healer and tribunal, the spirit grants health, peace, and settles disputes while upholding righteousness. After consuming the offerings, the appeased spirit promises continued protection. Exhausted after hours of performance, the medium sits and fans himself with a chamara. Devotees approach for blessings, receiving touches from his sword and taking home kumkum and pingara – betel nut flower as prasada.

Ritual Implements

Essential objects include:

- Ghante (bells) for invoking the spirit

- Swords and weapons, often gold-plated for important Daivas

- Ceremonial costumes with elaborate ornamentation

- Jeetige (torches) used during fire rituals

- Gejje (ankle bells) worn by the Patri

- Goblets for offerings and oil lamps

Offerings and Sacrifices

Offerings vary by region and specific Bhoota but typically include:

- Rice and other grains

- Meat (for certain Bhootas)

- Alcohol

- Fruits and flowers

- Money

Some Daivas, like Kodamantaye, abstain from animal offerings and are purely vegetarian, reflecting different spiritual philosophies within the tradition.

Agricultural and Sporting Connections

Bhoota worship maintains strong connections with agricultural life. Many ritual implements come directly from farming tools, emphasizing the practice’s roots in agrarian society. Traditional sports and activities are also integrated into celebrations:

- Kambala – Buffalo racing in muddy fields

- Kori Anka – Cockfighting

- Nagaradhane – Serpent worship

- Stone lifting competitions

These activities, while now independent events, originated within the Bhootaradhane tradition, demonstrating how the practice influenced broader cultural expressions.

Contemporary Relevance and Preservation

Despite modernization, Bhoota Kola remains a living tradition rather than a museum piece. Rural communities continue conducting annual ceremonies, and families gather to participate in worship, feast together, and seek guidance for the year ahead.

The tradition’s survival demonstrates its continued relevance in addressing community needs. Whether dealing with agricultural concerns, family disputes, or seeking protection from natural calamities, devotees maintain faith in the Bhootas’ ability to intervene positively in their lives.

Challenges and Adaptations

Modern practitioners face challenges in preserving this art form:

- Younger generations migrating to urban areas

- Diminishing knowledge of Paddanas and ritual procedures

- Environmental changes affecting traditional worship practices

- Balancing authenticity with contemporary contexts

However, the global massive movie success of Kantara has renewed interest among younger Tuluvas, many of whom are now actively learning Paddanas and understanding their cultural heritage.

The Broader Cultural Context

Bhoota Kola exists within a rich ecosystem of coastal Karnataka’s folk traditions, including Yakshagana (dance-drama), Nagaradhane (serpent worship), and various agricultural festivals. Together, these practices create a comprehensive cultural framework that has shaped Tuluva identity for centuries.

The tradition represents more than religious practice – it’s a complete worldview encompassing justice, entertainment, art, music, dance, and social organization. The elaborate costumes, the hypnotic music, the physical prowess of performers, and the dramatic narratives combine to create a total theatrical experience that rivals any formal stage production.

Bhoota Kola practice embodies principles of social equality, environmental consciousness, and community solidarity that resonate even in modern contexts. As Kantara showed the world, these traditions carry universal themes of justice, identity, and the human relationship with nature that transcend cultural boundaries.

Travel Tips for Visiting Locations for Bhoota Kola in Karnataka

Primary Locations for Bhoota Kola

Bhoota Kola ceremonies are predominantly performed in the coastal belt of Karnataka, spanning across specific districts and regions:

Dakshina Kannada District

- Mangaluru (Mangalore) – The cultural hub with numerous temples and shrines

- Bantwal – Known for traditional practitioners and authentic ceremonies

- Puttur – Rural areas with strong Bhoota worship traditions

- Sullia – Remote villages practicing ancient rituals

- Belthangady – Home to several prominent Bhoota shrines

Udupi District

- Udupi town and surrounding villages

- Kundapura – Particularly in Hiriadka and nearby areas

- Karkala – Known for the Kalkuda Kallurti Bhoota worship

- Brahmavara – Traditional coastal communities

Kasargod District (Kerala border region)

- Areas between River Chandragiri and the Karnataka border

- Villages maintaining the Tulu cultural practices

Notable Temples and Shrines

Several temples in coastal Karnataka are renowned for their Bhoota Kola performances:

Shree Veerabhadraswamy Temple, Hiriadka – One of the prominent temples in Kundapura, Udupi district, known for elaborate Bhoota idols and regular Kola ceremonies.

Kadri Manjunatha Temple, Mangaluru – While primarily a Shiva temple, it hosts Bhoota worship rituals.

Dharmasthala – Though famous for its Jain and Hindu temple, the region around it practices traditional Daiva worship.

Polali Rajarajeshwari Temple – Near Mangaluru, this ancient temple incorporates Bhoota worship elements.

Festival Season and Timing

Bhoota Kola ceremonies typically follow a seasonal calendar:

Peak Season: December to May

- Most Kola ceremonies occur during these months

- After the harvest season when communities have time for celebrations

- Cooler weather makes night-long ceremonies more comfortable

Major Festival Periods

- Makara Sankranti (January) – Many communities conduct annual Kola

- Dasara/Navaratri (September/October) – Some regions perform special ceremonies

- Regional festivals – Each village has specific dates based on their Daiva’s calendar

- Kambala season – Buffalo races often coincide with Bhoota worship activities

How to Witness Authentic Ceremonies

Bhoota Kola ceremonies are not commercialized tourist events and maintain their sacred, community-focused nature. However, they are not restricted to specific communities or castes, and visitors are welcome to observe with proper respect.

Practical Tips for Visitors

- Contact local hosts – If staying in Mangaluru, Udupi, or surrounding areas, ask your hotel or homestay owners about upcoming ceremonies

- Village tourism homestays – Coastal village homestays often know about local Kola schedules

- Temple inquiries – Contact major temples in the region for annual Kola dates

- Cultural organizations – Tulu cultural associations in cities like Mangaluru can provide information

- Timing – Ceremonies typically begin late evening (8-9 PM) and continue until early morning

- Respect protocol while Photography- Maintain silence during sacred moments, avoid flash photography, dress modestly.