Urupaanar at the Rasoham Kutty Kutchery Festival, Chennai: A Mesmerizing Performance Featuring Ancient 2,000-Year-Old Instruments from the Sangam Era—the Yazh (Yal), Parai, Kudamuzha, Kuzhal, Thudumbu, and Kombu | Performing from Their Debut Album ‘Thol’ – South India’s Ancient Sonic Cartography | Discover How This Contemporary Tamil Music Collective Revives Extinct Instruments Mentioned in Tolkappiyam

– bridging ancient tamil musical traditions with modern audiences

| CasualWalker’s Rating for Uru Paanar Performance at Rasoham Kutty Kutchery Festival : | |

9.9 – Extraordinarily Magnificent |

|

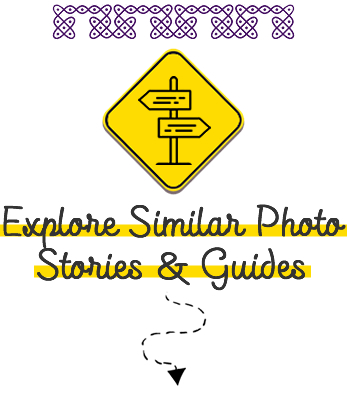

The Kutty Kutchery Festival has quietly transformed how Chennai experiences Carnatic music during Margazhi season, offering something beautifully different from traditional sabha concerts. Founded by Laasya Narasimhachari through Rasoham, this innovative festival creates “performative conversations” in cozy, intimate venues like cafés, art galleries, and rooftops with just 50-100 art lovers. Unlike formal concert halls where audiences maintain respectful distance, KKF dissolves that invisible wall—musicians don’t just perform, they share their journeys, inspirations, and craft in genuine dialogue with listeners.

The festival’s third edition presents 10 diverse genres across venues like Narthaki Studio and Vinyl and Brew, featuring Carnatic maestros, Kuchipudi dancers, tribal folk ensembles, Portuguese Fado, shadow puppetry, and more. Each 75-minute session transforms the Indian classical music experience into something accessible and transformative.

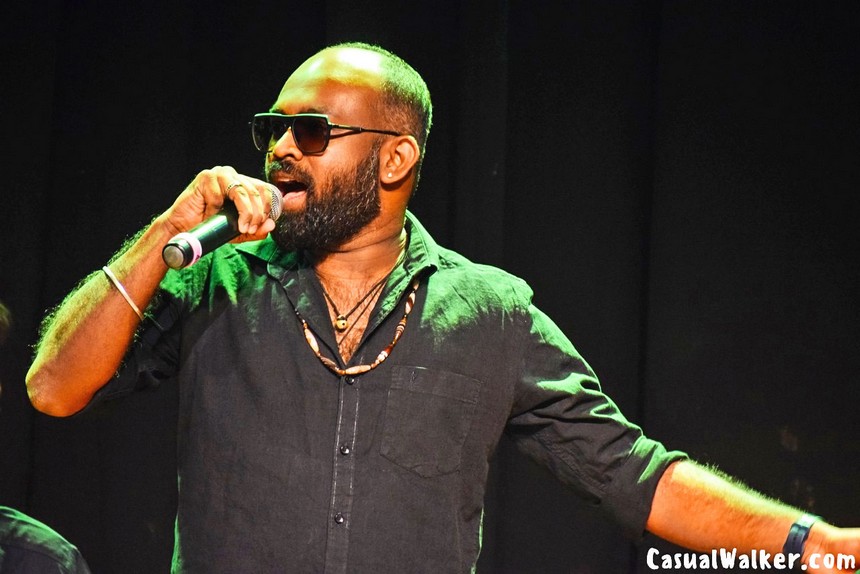

Uru Paanar: Resurrecting the Lost Sounds of Tamil Nadu

Among all the incredible performances this year, one ensemble has captured my complete attention: Uru Paanar. At the Rasoham Kutty Kutchery Festival, this contemporary Tamil music collective delivers a mesmerizing performance featuring ancient 2,000-year-old instruments from the Sangam Era—the Yazh (Yal), Parai, Kudamuzha, Kuzhal, Thudumbu, and Kombu. Through their debut album “Thol”—South India’s ancient sonic cartography—they present a traveling set of seven evocative songs. But true to the festival’s spirit, this isn’t just a performance. Their performance weaves together live music with conversations, stories, and reflections about how they’ve revived extinct instruments mentioned in Tolkāppiyam, bringing these ancient sounds back to life.

Band That’s Rewriting Tamil Music History

Uru Paanar is an eight-member contemporary Tamil music band-collective that has dedicated itself to reviving extinct musical instruments from the Sangam era, breathing life into sounds that have been silent for over a thousand years.

The name itself comes from Tolkāppiyam, Tamil literature’s earliest known text on grammar and culture. Through their music, they’re not performing history; they’re making history audible again.

Instruments That Time Forgot

Walking into an Uru Paanar performance feels like stepping into a living museum. The visual presence of their instruments alone is mesmerizing:

Yaazh – The crown jewel of their collection. This harp-like instrument features in Sangam literature and comes in multiple variations. Tharun’s first creation was the seven-stringed Sengotti Yazh. Today, Uru offers seven distinct Yaazh variations, including the magnificent seven-and-a-half-foot Peri Yazh crafted from Red Cedar and Kalimarudhu wood.

What distinguishes the yaazh from modern harps is its veterinum—the resonating chamber that produces a unique, soul-stirring sound that simply doesn’t exist in contemporary instruments.

Kudamuzha – This five-faced percussion instrument is mentioned in Sangam literature as a treasured musical tool. While an authentic 1,000-year-old playable Kudamuzha exists in Thiruvarur temple, it weighs 200 kg and stands 3.5 feet tall, making performances nearly impossible. Uru has ingeniously redesigned it for modern stages while maintaining its authentic sound.

Kuzhal, Thudumbu, Kombu, and Parai – These wind and percussion instruments complete the ensemble, each carrying centuries of Tamil musical heritage in their design.

The Uru Panar band also incorporates traditional instruments like Ghatam and Salangai, alongside three varieties of Yaazh, creating a textured sonic landscape that stays true to classical Tamil musical aesthetics.

The Visionaries Behind the Revival

The story begins with Tharun Sekar, a 27-year-old architect-turned-instrument-maker. Six years ago, when he couldn’t find a lap steel guitar in his hometown Madurai, instead of settling for alternatives, he decided to build instruments himself. But not just any instruments—he chose to resurrect those whose sounds had “faded into oblivion.”

In 2014, Tharun founded Uru Custom Instruments with a bold mission: modernize lost Indian instruments and make them accessible to contemporary musicians. What started as a solo experiment evolved into a thriving studio on Akbarabad Street in Kodambakkam, where Tharun works alongside four friends—Asha, Praveka, Varshini, and Archit.

The musical journey gained momentum when Siva Subramanian (SiSu) approached Tharun for a custom yaazh. SiSu, then an assistant professor at Thyagaraja College of Engineering, was involved in the historic Keeladi excavations and deeply researching early Tamil musical traditions. Their shared fascination with ancient soundscapes sparked a creative partnership that would eventually birth Uru Paanar.

Together, they began bringing in more artists—friends and friends of friends—until the collective grew organically into a 10-member ensemble, all united by one extraordinary goal: to rediscover the Tamil musical soundscape that predates even the 8th-century Thevaram and Thiruvasagam.

Music of Five Landscapes

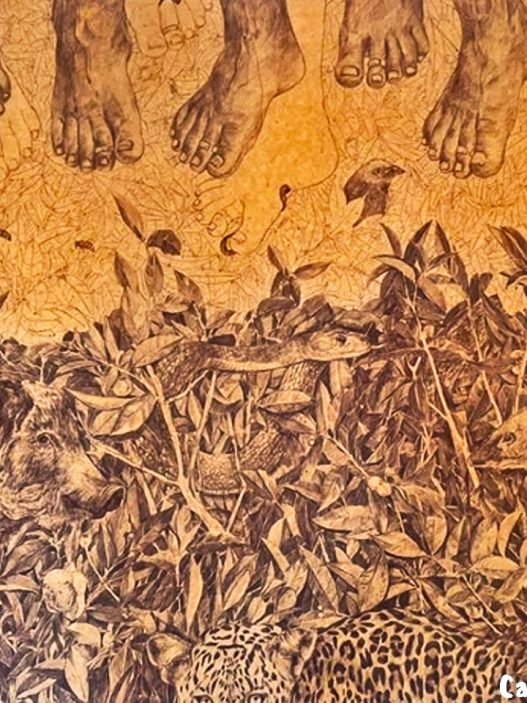

Uru Paanar’s music isn’t randomly composed—it’s deeply rooted in the Thinai concept from Sangam poetry. Each song embodies one of the five ancient Tamil landscapes with its associated emotions and times of day.

Their debut album “Thol” features seven evocative songs inspired by Tolkāppiyam. One standout piece is rooted in Mullai Thinai (pastoral landscape), unfolding during Maalai pozhudhu (evening time), interpreting Iruthal—the emotion of waiting. The pentatonic nature of the Mullai Pann (musical mode) creates a universality that resonates not just with Tamil traditions but with broader Southeast Asian musical cultures.

From the mournful oppari of Neithal (seaside landscape) to the tender intimacy of Mullai, each performance aims to transport audiences across Tamil Nadu’s ancient emotional and geographical terrains.

A Living Tradition, Not a Museum Piece

What strikes me most about Uru Paanar is their refusal to treat these instruments as museum artifacts. Out of their eight band members, only six are full-time musicians—the others come from different fields, yet they play confidently. This accessibility is intentional.

“These instruments are democratic,” Tharun insists. “As the world becomes more AI-driven, people will crave primitive, organic, human-made sound. Live music will only become more precious.”

They’re currently developing five new instruments inspired by Indian and Eastern traditions, with a list of 30-40 ancient instruments they hope to reconstruct. They regularly consult Tamil researchers and study historical sources to ensure authenticity before adding modern improvements for maintenance and playability. They’re also starting classes in Tambaram to teach people how to play these resurrected instruments.

Their vision extends beyond performances—they dream of establishing institutions to educate aspiring enthusiasts and expanding into a larger, more inclusive orchestra reflecting Tamil and Indian society’s rich diversity.

A Concert That Transcended Time

The ensemble that evening was extraordinary. Alongside the reconstructed yazh, talented musicians performed with the kanjira’s rhythmic pulse, the flute’s melodious whispers, the kombu’s powerful calls, the kokkarai’s distinctive tones, the sangu’s sacred resonance, the peppa’s earthy voice, and the parai’s commanding beats. Each traditional South Indian instrument contributed to a soundscape that felt both ancient and alive.

Art of Bringing History to Life

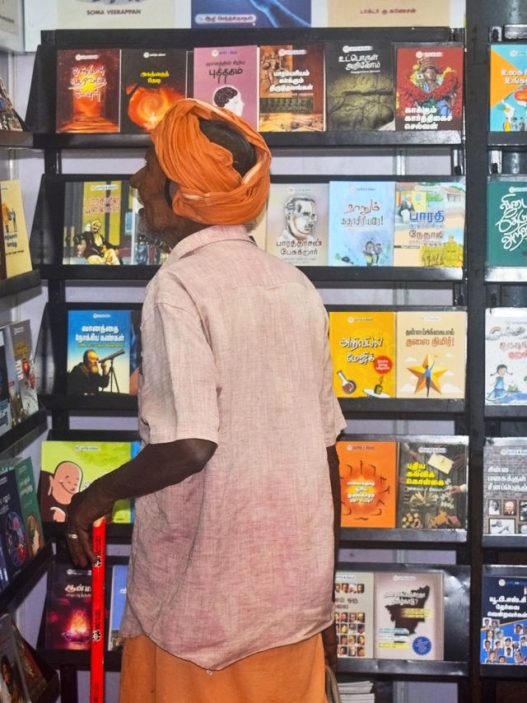

What truly captivated me was learning about Uru’s meticulous approach to reconstructing the yazh instrument. They didn’t simply guess or improvise—they became scholars, immersing themselves in precious Sangam literature like ‘Thirumurugatrupatai’ and ‘Sirupanatruppatai’. These ancient texts revealed not just technical specifications, but the soul of the instrument itself.

The original ancient Indian string instruments were masterpieces of organic design. Craftsmen shaped yazhs after nature’s most beautiful forms—peacocks with their regal bearing and fish with their fluid grace. The number of strings varied, each configuration producing unique tonal possibilities that ancient Tamil musicians explored with devoted creativity.

Honoring Tradition While Embracing Modern Ethics

Here’s where the reconstruction becomes even more inspiring. Historically, the yazh was crafted from red sandalwood and deer skin—materials that are now rightfully protected. Rather than compromise the project, Uru found thoughtful alternatives: goat skin and red cedar wood. This choice demonstrates profound respect for both ancient musical instrument preservation and contemporary environmental consciousness.

But Uru didn’t stop at faithful reproduction. Every reconstructed yazh they create is electric! Imagine—a 2000-year-old traditional Indian harp design that can connect to a DI unit or effects pedal. This brilliant fusion allows the yazh ancient instrument to speak to modern audiences while maintaining its historical authenticity.

Why we Should Experience This

In a world drowning in digital perfection and auto-tuned uniformity, there’s something profoundly moving about hearing sounds that haven’t been heard for centuries. Uru Paanar’s music isn’t just entertainment—it’s cultural archaeology made audible, history transformed into melody.

For anyone passionate about world music instruments and ethnomusicology, the work Uru is doing represents something precious. They’re not creating museum pieces meant to gather dust behind glass. They’re building playable, adaptable instruments that can participate in contemporary music while carrying forward an unbroken artistic lineage.

The success of the Uru Paanar event proves there’s genuine appetite for these sounds. Modern listeners are hungry for authenticity, for musical experiences that connect them to deeper roots. The ancient Tamil music revival isn’t backward-looking—it’s a vital, forward-thinking movement that enriches our entire musical landscape.

And experiencing it at the Kutty Kutchery Festival adds another layer of magic. The intimate setting, the conversational format, the proximity to artists who are literally making history—this is Margazhi reimagined for the 21st century.

As someone who grew up listening to Carnatic music in traditional sabhas, I never expected to find such innovation within our classical traditions. But that’s exactly what makes this special. This isn’t fusion for fusion’s sake or modernity rejecting tradition. This is tradition rediscovered, research made resonant, ancient aesthetics meeting contemporary accessibility.

Whether you’re a Carnatic music connoisseur, a folk art enthusiast, a history buff, or simply someone curious about Chennai’s evolving cultural landscape, the Kutty Kutchery Festival—and especially Uru Paanar’s performance—offers something genuinely unique.

These aren’t just concerts. They’re conversations across centuries. They’re proof that our heritage isn’t static but alive, waiting to be rediscovered, reinterpreted, and celebrated anew. Because some sounds are too precious to remain silent.