Mylapore Heritage Walk : Exploring Nooks of Mylapore in Chennai, Old Mylapore Through Kutchery Road, Agraharam Streets, Old Post Office, Mylapore Police Station, Traditional Artisan Quarter, Goldsmith Streets, Buckingham Canal & Colonial Mylapore Landmarks with K R Jambunathan at Sundaram Finance Mylapore Festival 2026 – Visit, History & Complete Travel Guide

– an unforgettable trail through the forgotten streets & lanes of old mylapore

| CasualWalker’s Rating for Mylapore Heritage Walk – Nooks of Mylapore : | |

9.8 – Exceptional Heritage Experience |

Mylapore Festival 2026, organized by Sundaram Finance and curated by Mylapore Times media, brought together heritage enthusiasts for an unforgettable exploration of Mylapore agraharams, the forgotten trading routes of colonial Madras.

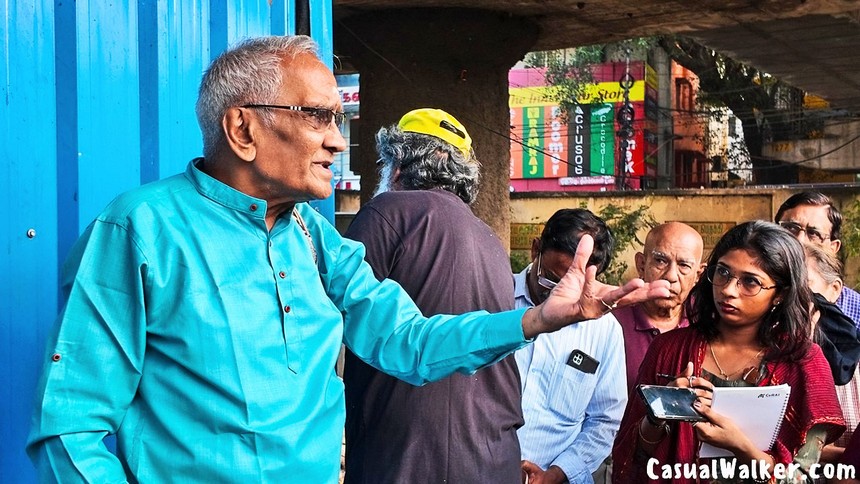

I recently embarked on an extraordinary Mylapore heritage walk called the Nooks of Mylapore Walk – that transformed my understanding of this sacred neighborhood. This wasn’t just another touristy stroll – this was a deep dive into the hidden corners of Mylapore, the lesser-known streets of Old Mylapore that we rarely discover. What made this Mylapore walking tour truly special was our guide – the Sri K R Jambunathan, an 70+ years young Guardian of Mylapore’s Living History. Walking with him felt like traveling with a time machine.

He was an former State Bank of India employee, was born and raised on Kallukaran Street in Mylapore – one of the oldest residential streets in this ancient quarter of Chennai city. Having spent seven decades in these winding lanes, He isn’t just a resident; he’s a living encyclopedia of Mylapore heritage. We are was also accompanied by Sri Vincent D’Souza, the founder of Mylapore Times and a curious explorer.

Exploring Mylapore’s Nooks, Crannies, and Forgotten Corners

Our heritage walk in Mylapore began at Kutchery Road, the administrative nerve center of old Mylapore, and wound through traditional acharis zones (artisan quarters), goldsmith streets, agraharam lanes, and canal-side markets that once pulsed with the commerce of colonial Madras. This was a journey into the lesser-known corners of Mylapore that reveal the neighborhood’s authentic soul.

1. Buckingham Canal: The Ancient Lifeline of Mylapore’s Trade and Transportation

Our first stop was the historic Buckingham Canal in Mylapore – a landmark heritage site that’s both architecturally significant and historically profound. This 19th-century canal system in Chennai wasn’t just a waterway; it was the economic artery of old Madras.

Historical Significance of Buckingham Canal

The Buckingham Canal, constructed during the British colonial period, stretched over 400 kilometers, connecting various coastal towns. In Mylapore, it served as the primary trading route for essential commodities. Jambunathan sir painted a vivid picture: boats laden with casuarina timber from coastal forests, fresh fish from fishing villages, seasonal vegetables from nearby farms, and salt from coastal salt pans would dock at Thanithurai market – the bustling boat landing point that served as Mylapore’s commercial heart.

Mahakavi Subramania Bharathiyar Connection

Mahakavi Subramania Bharathiyar, the legendary Tamil poet and freedom fighter, used this very canal to move to Pondicherry where he continued his revolutionary writings.

Engineering Marvel

Jambunathan sir explained an often-overlooked engineering brilliance: Mylapore never experienced water logging like other parts of Madras because the canal system provided excellent drainage. However, navigating the canal was challenging due to its narrow passages, requiring skilled boatmen who knew every turn and shallow patch.

2. Old Post Office Building: Where Madras Connected to the World

The Old Post Office on Kutchery Road Mylapore is a beautiful colonial-era building that once served as Mylapore’s communication hub. Jambunathan sir’s eyes lit up as he recalled the building’s glory days.

Historical Significance

This wasn’t just a post office – it was where Public Call Office – the PCO booths, connected families, where trunk calls were booked hours in advance, and where telegrams announced births, deaths, weddings, and emergencies. The telegraph service in old Madras made this building a vital node in the communication network that connected Mylapore to the rest of India and the world.

Agricultural Heritage

Behind this building once sprawled extensive spinach gardens and vegetable farms. These greens were harvested and sold in large winnowing fans (muram) and brass plates, then transported via the canal to markets across Madras. The agricultural history of Mylapore is often forgotten in our image of this temple town, but it was very much a farming community.

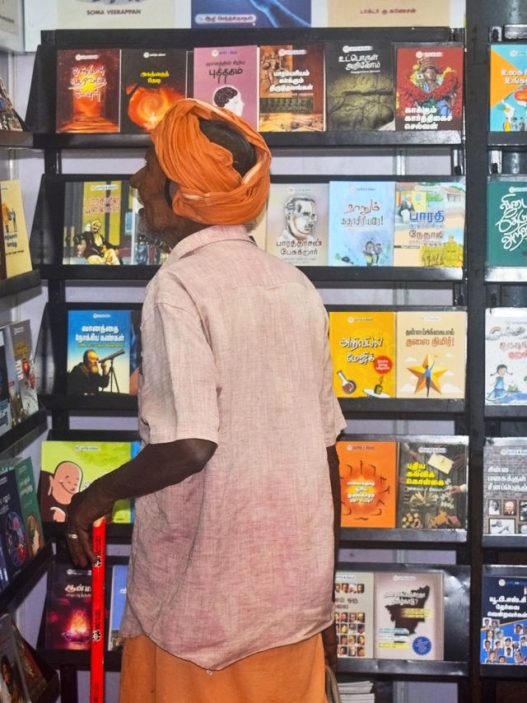

3. Nataraj Nillam: The Birthplace of Tamil Journalism

Opposite the post office stands Nataraj Nillam, a building that holds immense significance in Tamil journalism history. This was once the residence of Padamma Subramaniam, and more importantly, this is where Dina Thanthi – one of Tamil Nadu’s most influential newspapers – first began its publication. This space currently houses a wedding invite press.

Significance of Dina Thanthi

Founded in 1942, Dina Thanthi became the voice of the common man, covering local news, social issues, and political developments with a focus on Tamil culture and regional identity. That it started in a humble house in Mylapore speaks to the neighborhood’s intellectual and cultural vibrancy. This heritage building in Mylapore witnessed the birth of a media empire that would shape Tamil journalism for generations.

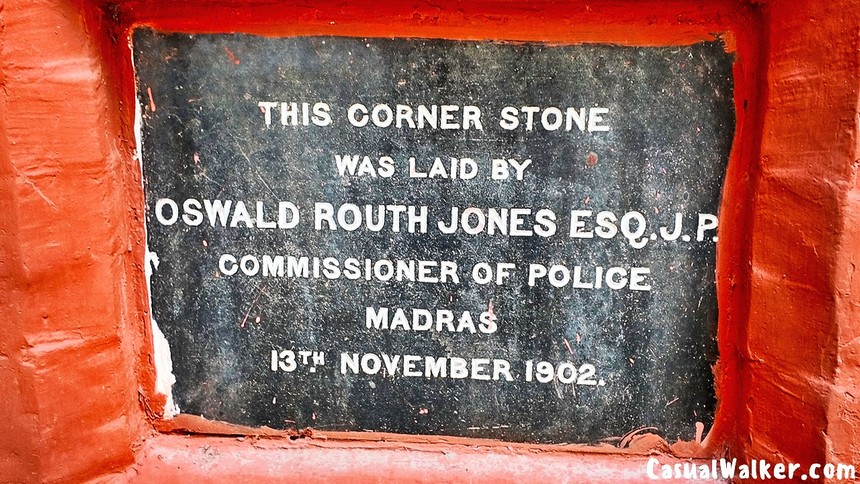

4. Mylapore Police Station: A Restored Colonial Gem

The Mylapore Police Station is a stunning example of colonial architecture in Chennai and a rare success story of heritage preservation in India. Built in the distinctive Indo-Saracenic architectural style that characterizes many British-era buildings in Madras, this police station features beautiful arched doorways, thick walls, and excellent ventilation systems.

Historical Importance

The station was officially opened in 1902 by Oswald Routh Jones, Esq., J.P., Commissioner of Police of Madras. The plaque commemorating this opening still exists – a tangible connection to colonial law enforcement in Madras. Jambunathan sir emphasized how fortunate we are that this building was preserved and restored rather than demolished, unlike many other heritage structures in Chennai that fell victim to urban development.

The building is contemporary with other administrative buildings of colonial Madras, sharing the same architectural language that includes high ceilings, large windows, and prominent entrances – all designed for the hot and humid climate of Chennai.

Red Post Box: A Fading Icon of Communication

A beautiful red post box stands quietly on the corner of the Mylapore Police Station, once the heartbeat of communication in India and increasingly hard to find these days. Spotting this rare survivor filled us with genuine excitement, a tangible connection to a bygone era right before our eyes.

These iconic structures, painted in their distinctive crimson shade, are more than mere mailboxes—they are living monuments to India’s heritage and the evolution of its postal system. Today, however, they often go unnoticed, fading into the background of our fast-paced digital world, their beauty and historical significance largely ignored by hurried passersby.

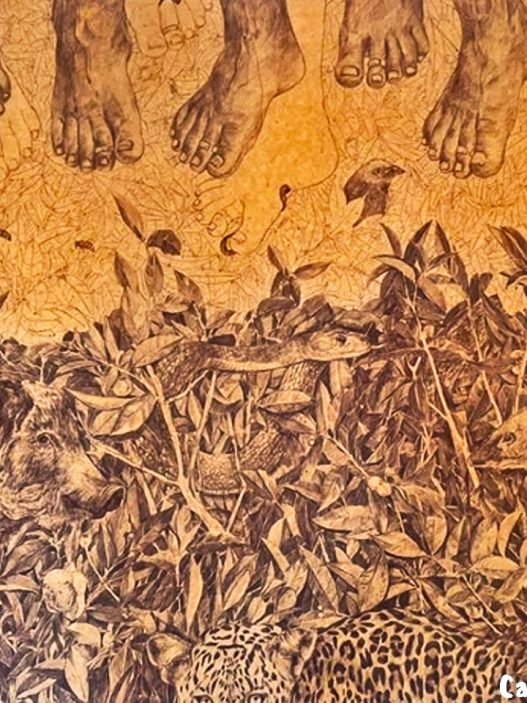

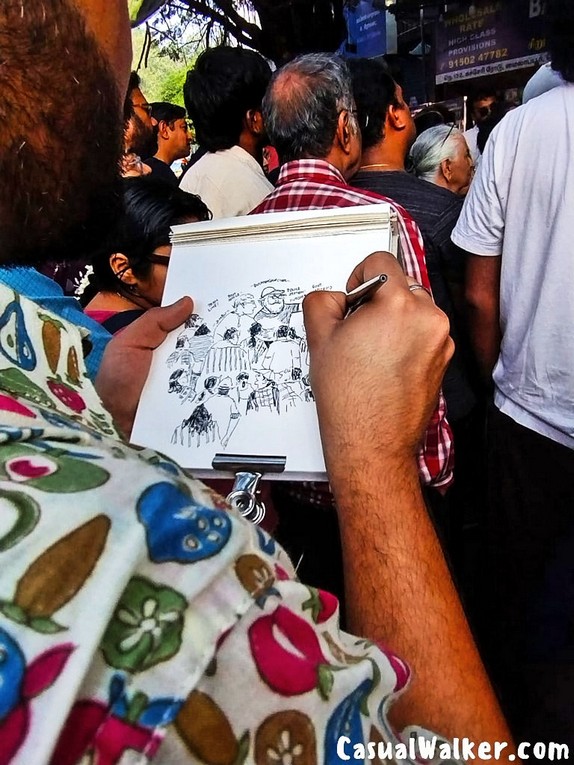

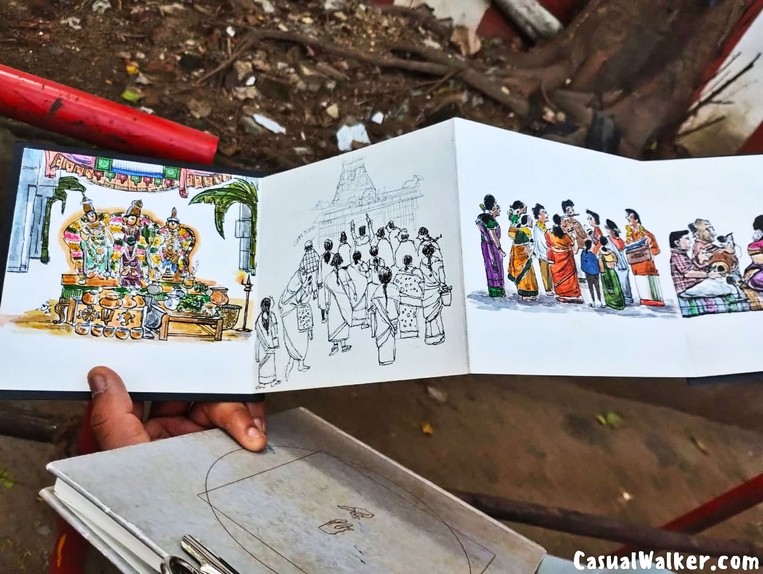

Capturing Heritage Walk Through Beautiful Sketches

During the walk, I happened to stumble upon a beautiful sketch by Srikkanth Balasubramanian, an Urban Sketcher and Illustrator based out of the Netherlands, that perfectly captured the essence of our Mylapore heritage walk experience.

The artwork was breathtaking in its attention to detail – it beautifully visualized the personas who joined our walk with remarkable artistic finesse. I was genuinely excited to discover his amazing work – there’s something truly special about seeing heritage and culture interpreted through an artist’s eyes, where every stroke tells a story and every shading captures an emotion.

His artistic interpretation of people, heritage sites, cultural landscapes, and spiritual spaces brings alive in ways that photographs sometimes cannot. You can explore more of his beautiful sketches on his Instagram page, where he consistently shares visual narratives of various rich cultural tapestry and heritage locations. His portfolio is a treasure trove for anyone passionate about Indian heritage, traditional architecture, and the art of storytelling through sketches.

5. Venkataraman Ayurveda Dispensary: Traditional Healing Heritage

Our next stop was the Venkataraman Ayurveda Dispensary, a traditional massage and treatment center that represents Mylapore’s ayurvedic heritage. Ayurveda in Mylapore has deep roots, with several vaidya families (traditional physician families) having practiced here for generations. Sri V.Krishnaswami Iyer was the founder of the Venkataramana Ayurveda College & Dispensary, The Madras Sanskrit College and Indian Bank.

These ayurvedic centers in old Madras weren’t just treatment facilities; they were centers of traditional medical knowledge, where ancient healing practices were passed down through generations. The panchakarma treatments, ayurvedic massages, and herbal medicines prepared here connected patients to a 5,000-year-old healing tradition.

6. Tram Stop: When Mylapore Moved on Rails

Standing at what was once a tram stop in Mylapore, I tried to imagine the clanging bells and rumbling wheels of the Madras tramway system. Jambunathan sir described with animated gestures how the tramlines passed through Luz Circle – the major transport hub – connecting Mylapore to the rest of Madras.

Tramway Network

The tram routes in old Madras extended all the way to Santhome High Road near the beach, where you now find fishermen’s quarters. This coastal terminus was strategically important because near the beach stood a radio communication hub – part of the maritime communication system that connected ships to shore.

The Madras tram system, operational from 1895 to 1953, was an engineering marvel and the first electric tram service in India. For Mylapore residents, the tram was the lifeline to Georgetown, Egmore, and Triplicane – the commercial and administrative centers of colonial Madras.

Why the Trams Disappeared

The closure of the Madras tram network in 1953 remains controversial. While officially attributed to high operational costs and road traffic congestion, many believe it was a mistake that cost Chennai an excellent public transport system. Today, as Chennai grapples with traffic nightmares, heritage enthusiasts often lament the lost tramways.

7. Amman Koil Street: The Goldsmith Quarter of Mylapore

Amman Koil Street represents one of the most fascinating aspects of traditional urban planning in Madras – the concentration of specific craft communities in designated streets. This was the goldsmith quarter of Mylapore, where generations of Ashari families- the goldsmith communities lived, worked, and prospered.

A Hub of Goldsmiths

Not long ago, home-based goldsmiths dominated this area off Sri Mundagakanni Amman Temple. They employed men to work in the thinnai (front porch) or in the front section of their houses. If you walked down this main street then, you could faintly spot the goldsmiths at work in large, tiled houses.

What’s fascinating is that jewels were not sold here – unlike what we now see in the heart of Mylapore with its large jewelry stores. These were purely workshops where master craftsmen created exquisite pieces.

Historical Significance

The practice of craft-based street settlements is ancient in India. Goldsmiths in Mylapore weren’t just jewelers; they were artists and metallurgists who created the temple jewelry, wedding ornaments, and sacred items that formed an integral part of South Indian culture.

Sastry & Sastry was one of the most famous goldsmith establishments here, known for traditional jewelry designs and excellent craftsmanship. These weren’t modern jewelry stores; they were workshops where master craftsmen trained apprentices in techniques passed down through generations.

Architectural Heritage

Jambunathan sir pointed out the distinctive 1+1 houses (one room on the ground floor, one on the first floor) with Mangalore-tiled roofs – the typical artisan housing in old Mylapore. These modest homes had small street-facing workshops where goldsmiths worked while passersby watched the intricate process of jewelry making.

The street walls were plastered with handwritten posters announcing temple festivals, cultural programs, death announcements, and community meetings – the traditional social media of Mylapore that still functions in parallel with modern communication.

Mayanakolai – Cremation Ground

At the end of the road, near the Kolaveli Mundakanni Amman Temple, stood the community cremation ground (mayanakolai). The presence of a cremation ground adjacent to residential areas might seem unusual to modern sensibilities, but in traditional Hindu town planning, death was accepted as part of life’s cycle, not hidden away.

8. Dojo Kulfis and Ice Cream Shop

The Dojo Kulfi and Ice Cream Shop, located opposite the Draupadi Amman Temple en route, is a beloved traditional ice cream parlor that has served generations of Mylapore residents.

Kulfi, the traditional Indian ice cream, has been made in Mylapore for over a century. Unlike modern ice cream, kulfi is denser and creamier, made with reduced milk, sugar, and traditional flavors like cardamom, saffron, pistachio, and rose. This shop represents the culinary heritage of Mylapore – simple pleasures that have survived the onslaught of modern franchises.

9. Banumoorthy Agraharam – Mundakanni Amman Street 5th Lane:

This is where the heritage walk became truly special – entering the traditional Brahmin agraharams that define Mylapore’s unique character.

Banumoorthy Legacy

Jambunathan sir shared a fascinating story: one of the famous goldsmiths in the oldest times, called Banumoorthy, did so well in the business that he came to own an entire agraharam. This colony, known as Banumoorthy Agraharam, still exists today on Mundakanni Amman Street 5th Lane – a testament to how successful artisan entrepreneurs could become property owners and community builders.

These goldsmiths were famous city-wide and had a large clientele. They would visit their clients, decide on the designs, make the jewels, and deliver them. In some cases, families hosted the goldsmiths for some days, so that the jewels could be crafted at their residence – a practice that speaks to the intimate relationship between artisan and patron in old Madras.

What is an Agraharam?

An agraharam is a traditional Brahmin residential quarter, typically a street lined with identical houses on both sides, with a temple at one end. The Banumoorthy Agraharam is a perfect example of this ancient urban design.

Architectural and Social Significance:

Agraharams in Mylapore represent a unique urban planning philosophy that prioritized spiritual focus, community living, and shared resources. The identical houses created social equality among residents, while common wells, courtyards, and spaces encouraged community interaction.

Goldsmith Families

Interestingly, on the opposite side of the road lived goldsmith families – showing how different communities coexisted in Mylapore. The Brahmins provided priestly services and education, while the Asharis (goldsmiths) created the beautiful temple jewelry and ritual objects. This economic interdependence created a vibrant neighborhood ecosystem where craft and culture flourished together.

10. Kallukaran Street

Kallukaran Street holds special significance because this is where our guide, K R Jambunathan, was born and raised. Walking these lanes with him felt like stepping into his personal memory book – every corner held a story, every house had a history.

Name Controversy

The name “Kallukaran” literally translates to “stone workers” in Tamil, leading to two theories about the street’s origins:

Stone Sculptors – Some historians believe stone sculptor families (silpi communities) lived here, crafting the intricate sculptures for Kapaleeshwarar Temple and other temples in Mylapore. The stone carving tradition in Tamil Nadu is ancient and revered, with sculptors enjoying high social status for their role in temple construction.

Toddy Tappers – Others suggest “Kallukaran” refers to toddy tappers (Kallu), people who climbed palmyra and coconut palms to collect toddy (fermented palm sap).

Nyniappa Mudaliar Connection

The street is also historically significant because Nyniappa Mudaliar, one of the three founders of Nageswara Park, lived here. This connection illustrates how Mylapore residents contributed to urban development in colonial Madras, creating public spaces that still serve the community today.

Spiritual Significance

Jambunathan sir reminded us that Mylapore hosted both Alwars and Nayanmars – the Vaishnavite and Shaivite saint-poets whose devotional hymns form the bedrock of Tamil Bhakti literature. Walking these streets where spiritual giants once walked adds profound depth to the Mylapore pilgrimage experience. These Tamil saints composed immortal verses in these very lanes, transforming Mylapore into a sacred landscape of devotion.

11. Agraharam Lane: A Path to Hidden Temples

Opposite the Mundakanni Amman Temple runs a lane with an agraharam leading to the canal. This pathway tells a poignant story of how urban accidents can alter centuries-old routes and sever connections that once defined a neighborhood’s spiritual geography.

Blocked Pathway

Jambunathan sir explained that this pathway is partially blocked due to an accident. What’s significant is that this pathway once connected the Madhava Perumal Temple on the eastern side with the Mundakanni Amman Temple on the western gateway.

Temple-Agraharam Connection

This blocked path reveals the spatial logic of traditional temple towns. Agraharams were always built near temples because Brahmin residents were responsible for temple rituals, maintenance, and daily worship. The pathways between temples and agraharams were both spiritual and functional arteries, allowing priests to move between sacred spaces during festivals and daily worship routines.

The western gateway still opens into Mundakanni Amman Temple Street, but the connection to Madhava Perumal Temple is severed – a small tragedy of urban heritage loss that goes unnoticed by most. Standing at this blocked pathway, I felt the weight of what’s been lost – not just a physical connection, but a living tradition of temple circuits that once animated these streets.

12. The Adjacent Agraharam Lane: Traditional Town Planning Genius

The lane adjacent to the blocked pathway showcases another set of well-preserved agraharams that demonstrate the genius of traditional South Indian architecture.

Ground Plan and Air Circulation

The well-laid pattern and ground plan allowed excellent air circulation – crucial in Chennai’s heat. Houses were designed with:

- Linear Layout: Houses lined up in perfect rows on both sides of a straight street

- Cross Ventilation: Every house had openings on both front and back, ensuring airflow through the hot Madras summers

- Central Courtyard: Many houses had open-to-sky courtyards (mutram) that acted as temperature regulators

- Narrow Streets: The narrow street width meant buildings on opposite sides shaded each other during midday

- Shared Walls: Common walls between houses reduced heat transfer

Temple-Owned vs. Private Houses

A fascinating aspect Jambunathan sir highlighted was the distinction between temple-owned and privately-owned agraharam houses:

Temple-Owned Agraharams

- Granted by temples to Brahmin priests and scholars as part of their compensation

- Residents had hereditary occupation rights but not ownership

- Maintenance responsibility fell on the temple administration

- Often poorly maintained due to temple financial constraints and legal complexities

Privately-Owned Houses

- Purchased or inherited through generations

- Better maintained as family property

- More likely to undergo modern renovations (sometimes destroying heritage features)

- Can be sold outside the community, leading to social character changes

The challenge of maintaining agraharam heritage lies in balancing residents’ rights to modern amenities with architectural conservation. Many temples in Chennai lack resources to maintain their heritage properties, leading to deterioration of these architectural gems.

Larger Heritage Context: Why Mylapore Matters to Our Culture

As we concluded our heritage walk through Mylapore, I reflected on why this experience matters beyond just tourist curiosity.

Mylapore as a Living Heritage Site

Mylapore is a living heritage – people still live in these century-old houses, still worship at these ancient temples, still shop at these traditional markets. This living heritage is both its strength (it remains authentic and functional) and vulnerability (it’s constantly under pressure from modernization).

Heritage walks in Mylapore, like the one organized by for Sundaram Finance Mylapore Festival 2026 and Mylapore Times media doing a invaluable work in preserving and sharing this intangible cultural heritage. Their enthusiasm and dedication remind us that heritage conservation isn’t just about preserving buildings – it’s about keeping stories alive, honoring ancestors, and creating meaningful connections between past and present.

Also, check out Our Similar Interesting Photo Stories :